Driving through Idaho on the way to Glacier NP, a sign just off the highway indicated to a place nearby that caught my attention. Taking a short detour off the road, I arrive to the Minidoka National Historical Site.

About the Minidoka National Historic Site

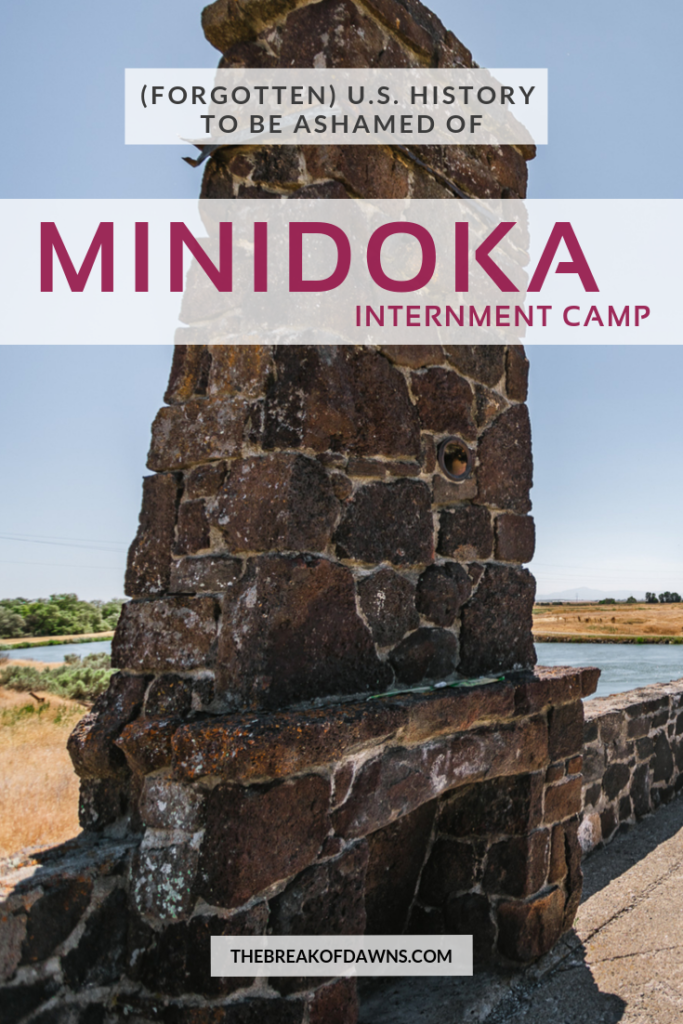

In the high desert plains east of Twin Falls, Idaho is what remains of an Internment Camp, now known as the Minidoka National Historic Site. Housing more than 9000 Japanese-Americans for 3 years during WWII, it was one of 10 camps like this throughout the country.

What’s Behind the Creation of this Camp?

While the United States essentially took a 2 year back seat to WWII, the December 7, 1941 Japanese air strike attacks on Pearl Harbor changed everything. Because of that event, the U.S. joined the ranks of those fighting in WWII. With xenophobia on the rise and fear of ‘enemy sympathizing,’ the government took an extreme step with initiating internment camps.

Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 into action. In turn, that gave power to the Secretary of War to establish military zones where citizens could be removed. It was now illegal for any person of Japanese descent to reside on the West Coast.

Although many Americans and politicians publicly disagreed, 9066 remained the law until 1944. The Supreme Court reversed the Executive Order in a case called Ex parte Mitsuye Endo. That decision found that 9066 was unconstitutional as the majority of those imprisoned were born in the U.S. and thus stripped of their rights on the sole basis of ethnicity.

Initiating Internment at Minidoka

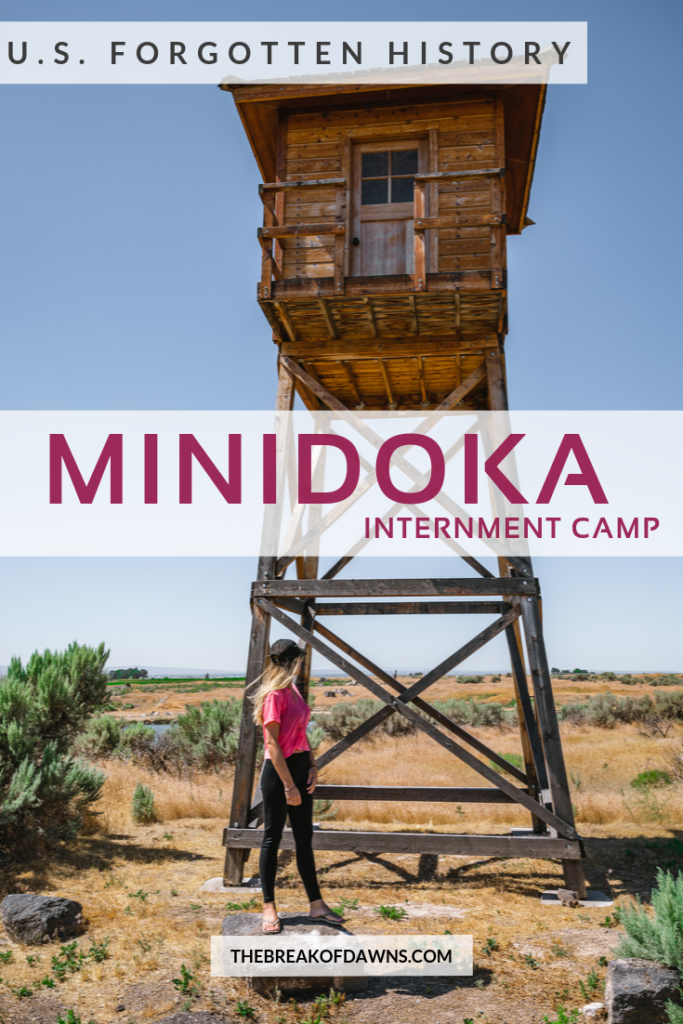

Once the Executive Order was signed, things moved fairly quickly. The Japanese-Americans were given short notice, from days to a couple weeks, to vacate the West Coast. During the construction of the camps, they were housed in temporary detention centers. Upon transferring them to the internment camps, they were placed on trains with the blinds pulled shut.

Executive Order 9066 stripped the lives from more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans.

Life at Minidoka

The Minidoka Internment Camp housed Japanese-Americans from Oregon, Washington and Alaska. Although many people arrived quickly, the sewage and plumbing wasn’t finished for months and housing was built poorly. Without insulation for warmth in Idaho’s harsh winter, the greenwood and tar paper offered citizens little relief.

One unit, complete with a single lightbulb and a charcoal stove, housed a family or group up to 9 people. With 6 units in one barrack and 12 barracks in a block, Minidoka’s 36 blocks housed nearly 9000 people. In each barrack was a dining hall and bathrooms, devoid of stalls or walls for privacy.

The only hope of escaping internment was by volunteering to serve in the military. More than 25% of all Japanese-Americans serving in WWII came from Mikidoka. Furthermore, they also experienced the worst casualty rate of any camp.

Minidoka National Historic Site and its Forgotten History

Discussing the Minidoka National Historic Site with my followers, I found that the majority of people knew nothing about it. When I recall this history lesson from high school, I was as shocked then as I am today that these ideologies exist in our history. How could a country so great be responsible for stripping the rights from its own people?

It’s important to remember significant pieces of our past and history, especially those that affected nearly 120,000 citizens. Bringing light to topics that have been forgotten about will help us learn from our mistakes.

Visit the Minidoka National Historic Site Friday through Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

“We retain the right to lead our individual lives as we please, but we can only do so if we grant others the freedoms that we wish for ourselves.” – Eleanor Roosevelt

Like This Post? Pin It!

| This post contains affiliate links. At no extra cost to you, if you purchase one of these products I may receive a small commission. This helps me maintain my blog as a free space to you. Check out my Disclaimer for more info.